As I approached the task of writing my first post of 2026, I thought I’d back up a bit. Rather than dive into a detailed deconstruction of, for instance, a prominent cancer researcher and cancer center director‘s very recent doubling down on arguing that the scientifically unsupported claim that COVID-19 vaccines cause “turbo cancers” is scientifically plausible (which I might have to address another time to explain again why it’s not), I thought I’d revisit a question that I’ve written about on several occasions over the last 20 years, both here and at my not-so-secret other blog, namely the question of whether it is ever worthwhile, effective, or a good idea for scientists, physicians, and science communicators to agree to debate science denying cranks. Longtime readers of this blog will know that I have long tended—with caveats—to come down on the “No!” side of this debate. Specifically, I’ve long viewed “live public debates” of this nature less as scientific debates and more as spectacles craved by science deniers to rally their supporters by providing their viewpoints with seeming legitimacy. Science deniers accomplish this by enticing real scientists to appear on the same stage with them, where they can Gish gallop and empty deceptive rhetoric to produce the illusion that there is a real scientific debate about, for instance, the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Scientists unprepared to confront Gish gallops and rhetoric over substance can stumble, sometimes badly, which is another reason why such debates tend to be a triumph of influencer “content” over substance. Indeed, nearly 13 years ago, I coined a corollary to crank magnetism that I dubbed, “All Truth Comes From Public Debate.”

I still believe that, in general, it’s usually a bad idea for scientists to agree to these sorts of debates (albeit perhaps less vehemently than before, and recognizing exceptions). However, I now feel that a couple of recent events make it worthwhile for me to revisit this question. The first was a post by our old “friend,” tech bro turned antivax influencer and activist Steve Kirsch, who attacked pediatrician and vaccine scientist Dr. Paul Offit for having declined a challenge to engage in a public debate about vaccines made by Kirsch, longtime antivax activist now sadly in charge of the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and his collaborating lawyer Aaron Siri, who recently wrote a book calling vaccines a “religion.” In his post, Kirsch, had offered Dr. Offit $1 million and, as tends to be his wont, tried to portray himself as the true champion of science and Dr. Offit’s refusal as being unscientific.

The second incident was the appearance of Mikhail “Dr. Mike” Varshavski, DO, a family medicine doctor who’s become a well-known YouTuber and podcaster, whose The Checkup with Dr. Mike boasts over 14 million YouTube subscribers and who is known for debunking health misinformation, on Surrounded. Surrounded, for those not familiar with it, is a very popular web series/YouTube show produced by the political YouTube channel Jubilee Media. Its gimmick is to pit one person against up to 25 “debate” opponents who are seated “surrounding” the main debater, who sits at a table in the center. Opponents take turns stepping into the center to sit in a chair across from the featured debater and “debate” him or her for a set time (complete with timer to say when time’s up). Most of the topics debated this way on Surrounded tend to be political, and recent episodes that I’ve briefly perused feature unpromising titles like Piers Morgan vs. 20 “Woke” Liberals, 1 Atheist vs. 25 Christians, 1 Journalist vs. 20 Conspiracy Theorists, 1 Liberal Teen vs. 20 Trump Supporters, and, a year ago, 1 Conservative vs. 25 Liberal College Students (Feat. Charlie Kirk), which appears to be the first episode ever of this series. However, occasionally the show looks at health-related topics, such as a previous appearance by Dr. Mike several months ago (Dr. Mike vs. 20 Anti-Vaxxers) and, less impressively, Bryan Johnson vs. 20 Skeptics. (Bryan Johnson, in case you don’t remember, is the wealthy biohacker who has been in the news for spending $2 million a year to reverse the clock using quackery such as transfusions with his son’s youthful blood, full plasma exchange, a boatload of unproven supplements and treatments, rapamycin for “anti-aging” and claims that he will achieve immortality by 2039.

Dr. Mike appeared on an episode of Surrounded in December entitled 1 Doctor vs 20 RFK Jr. Supporters, where, as the title says, he confronted 20 “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) supporters of our current HHS Secretary. I must admit that, before this episode, I had never been able to sit through an entire episode of Surrounded, and, I must also admit, that even I found it quite difficult to sit through all of Dr. Mike’s appearance. (The episodes tend to be 90 to 120 minutes long.) However, I have to concede that Dr. Mike acquitted himself extremely well, far better than I would have expected anyone to be able to do in such a format. As a result, I started to question, if just a bit, whether my stance regarding these sorts of “debates” has been too dogmatic, even as I realized that Surrounded is about as pure a distillation of “debate me, bro” culture as one will ever come across on social media. After all, if you peruse the list of Surrounded episodes, you will find that the producers appear not to care all that much about truth; they appear far more interested in generating spectacle, arguments, and sparks, the better to attract clicks and eyeballs.

On the other hand, Steve Kirsch’s clumsy, heavy-handed attempt to brand his desire for “live public debates” with scientists like Dr. Offit and Dr. N. Adam Brown, who had penned an article criticizing RFK Jr. for MedPage today (entitled provocatively, I Was Wrong About RFK Jr.), as “science-based” and Dr. Offit’s assertion that science is best debated in the peer-reviewed literature as unscientific reminded me what the real purpose of cranks wanting “live public debates” always is. I like to refer, for instance, to Neil deGrasse Tyson’s disastrous “debate” with antivax activist Del Bigtree as a counterexample and cautionary tale regarding such “live public debates.”

With this as the backdrop, I looked at the evidence regarding the effect of “live public debates” and whether there really is such a thing as the backfire effect, in which such debates supposedly reinforce, rather than weaken, the beliefs of science deniers. Unsurprisingly, Steve Kirsch, being Steve Kirsch, cherry picked evidence and commentary and, risibly, used AI to generate arguments for his position, as though AI were any authority. Even so, I found my position regarding these debates softening a bit, not because I suddenly think they’re a good idea, but rather because I don’t think we as science communicators can avoid them entirely.

Let’s start with Kirsch.

Quoth Steve “debate me, bro!” Kirsch: I’m the real champion of science. (He’s not.)

Three weeks ago, Dr. Offit posted an article on his Substack, with accompanying video, entitled Debating Science: No Thanks, where he added, “Anti-vaccine activists RFK Jr., Aaron Siri, and Steve Kirsch have asked that I debate them on vaccine safety. One of them offered me $1 million to do it. Here’s why I declined.” In his post, Dr. Offit asserted:

Several years ago, people representing RFK Jr., who at the time was head of the anti-vaccine group, Children’s Health Defense, offered me $50,000 to debate him about the safety of vaccines. In the past week, Aaron Siri, a personal-injury lawyer whose firm represents an anti-vaccine group called Informed Consent Action Network, also asked me to debate him. As did Steve Kirsch, an entrepreneur and co-inventor of the optical mouse, who offered me $1 million if I agreed. I turned them all down because it doesn’t matter what they say during the debate. And it doesn’t matter what I say. The only thing that matters is the strength and reproducibility of the evidence.

It must be said right here that this is almost exactly what I tend to say regarding such “debates.” One also must remember that Kirsch is a hard core conspiracy theorist about vaccines. Early in the pandemic he founded the COVID-19 Early Treatment Fund (CETF) in order to fund research into off-label treatments for COVID-19 using existing drugs already having FDA approval for other diseases. Unfortunately, his reactions to the results of his project, the good and the bad, were a major foreshadowing for the antivax heel turn that he would soon take. Refusing to believe the results of a study funded by CETF that found that hydroxychloroquine had no value treating COVID-19, he turned on the investigators, accusing them of poor study design and statistical errors. By mid-2021 Kirsch was promoting ivermectin as a miracle cure for COVID-19, that COVID-19 vaccines impair female fertility (they don’t), and that the mRNA vaccines were killing more people than they were saving—150,000 killed by the vaccines, according to him! By May 2022 he had upped that number to claim that mRNA vaccines had killed over a half a million people while only saving ~25,000.

By 2022, Kirsch had developed a penchant for challenging critics of COVID-19 quackery and antivax misinformation to live public debates, a penchant that led him to annoy the crap out of legitimate scientists by issuing fatuous “challenges” conveyed to them by email and publicly on his Substack. (I’ve been at the receiving end of a few.) Equally predictably, Kirsch’s anti-COVID-19 vaccine variety of antivaccinationism soon expanded to encompass “old school” antivax conspiracy theories, such as the CDC whistleblower conspiracy theory featured in the 2016 antivaccine propaganda “documentary” VAXXED (even more recently resurrected by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.) and, of course, the long debunked claim that childhood vaccines cause autism, all while using legal bullying and doxxing to silence critics. Indeed, his MO has been to offer scientists like Dr. Offit a million dollars (or to donate a million dollars to the charity of their choice) in return for “debating” him or someone chosen by him or to bet the chosen debater a large sum of money over the results of the debate. Unsurprisingly, he’s been accused of welching on at least one of his bets, leading Kirsch to dox him and threaten to sue him. One cannot forget this background when considering anything Kirsch says about debating scientists. Context matters.

But back to Dr. Offit. He made what I consider to be a reasonable response when faced with a “challenge” to a “debate” about vaccines from the likes of Aaron Siri, Steve Kirsch, and RFK Jr. Pointing out the distortions and misrepresentations of vaccine safety data by Aaron Siri and RFK Jr., he wrote:

Enter Steve Kirsch, who has said that Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine has “killed more people than it saved.” Great. Prove it. Do the kinds of epidemiological studies that were done for Guillain-Barré syndrome, intussusception, narcolepsy, and clotting. Do the hard work that’s required to prove that a vaccine safety problem is real and stop whining about Big Pharma and government conspiracies. Serious vaccine safety problems will be published if the data are rigorously collected, analyzed, controlled for confounding variables, subjected to peer review, and reproduced by other investigators. And they won’t be published if the data are weak. Vaccine safety is a scientific question that should be solved in a scientific venue, not on a debate stage.

Indeed. And it has been. However, that’s not what people like Kirsch, Siri, and Kennedy are about, and Dr. Offit knows it.

Which brings me to Kirsch’s response to Dr. Offit’s rejection, The peer-review literature says science should not run from public challenges; here’s a framework for fair discussions, in which he attempts to frame Dr. Offit’s refusal as being “antiscience” (as in “I know you are, but what am I?): “None of the people who claim RFK Jr is doing a bad job will consent to public challenge. That’s anti-science. Here’s a framework for fair public discussions on the most important issues of our time.”

He begins his “executive summary”:

None of the “experts” who think:

- RFK is causing harm

- that ACIP panel members are anti-science

- that the COVID vaccines have saved > killed

- that vaccines don’t cause autism or chronic disease

will come to the public discussion table to talk about it. That makes the problem worse, not better.

He then claims that he will “cover”:

- the evidence directly from the scientific literature that refusing debate challenges is anti-science

- how a fair public discussion should be structured

- how the peer-review system relied on by Paul Offit and others should be reformed (one of the most important articles I’ve written to date)

- my email to Dr. Brown pointing out that RFK Jr isn’t the problem; it’s that people like him refuse to engage in public discourse with qualified peers who have different views

I’ll take these out of order. Also, I’m not going to discuss #4 much. You can read Kirsch’s post, which contains a screenshot of the email, and see for yourself that the email is an attempt to shift the blame from people (like him) promoting medical misinformation to those refusing to engage in direct one-on-one live public debates with people promoting medical misinformation. Later in the post, Kirsch invokes AlterAI to deconstruct Dr. Offit’s Substack post, which never fails to amuse me whenever he does this. Seriously, dude, make your own arguments, rather than lazily prompting hallucination prone LLM-AI models to do your work for you.

As for #2, I might have to do a full post on his “proposals” to “reform” peer review at some point. However, Kirsch starts out with rants about peer review as “gatekeeping” (as though that were a bad thing), moaning that “Mainstream literature does not contain papers explicitly concluding that ‘vaccines killed more than they saved’ — because such framing will not pass peer review gatekeeping.” (I would argue in this case that gatekeeping is a good thing, because every such paper that I’ve read and deconstructed has been some of the most hellaciously bad science I’ve ever seen. Despite its shortcomings, review can work when it comes to truly bad science.) Kirsch then moves on to mixing some somewhat reasonable points (decoupling scientific publishing from corporate funding through advertising, for instance; I doubt very many scientists would disagree with the contention that big publishers might distort what is being published) with typical tech bro nonsense, like using blockchain to trace and track peer review and granting “equal access” to government datasets to science-denying cranks. (True, he calls them “independent researchers,” but I know what he really means.) Where we differ with Kirsch is that we don’t assume that this profit motive inevitably leads to the “suppression” of any data or studies that cast doubt on the safety and efficacy of vaccines, as Kirsch does. I’ve even said that a double-blind peer review process might be desirable, although I doubt that it will be always possible given that peer reviewers who are sufficiently expert in their fields to be asked to peer review a manuscript will very often be able to guess which lab or group of investigators produced a given study.

Overall, Kirsch’s criticisms of peer review and proposals for “reform” obviously derive from a science-denying antivax perspective full of typical narratives of big pharma “suppressing The Truth.” These include narratives about conventional scientists like Dr. Offit supposedly being closed-minded “gatekeepers” who reflexively reject brave mavericks like him who “question” the dominant narrative on vaccines, coupled with “prove me wrong” boasting about antivax misuse of various datasets and statistical malfeasance by antivax “scientists” to torture data into confessing what they want to hear.

More interesting is Kirsch’s statements on what a “fair” public debate. Again, as always, he mixes the reasonable with the not-so-reasonable. For instance, it is correct that a clear, narrow question is best. What he doesn’t mention is that the downside of that is that, if such a restriction is adhered to, not very much will be concluded, as the conclusion will be narrow. Of course, his example of such a “narrow” question (“Do current data justify the claim that mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective in adults under 40?”) is not narrow at all, when you start addressing the topic in depth! He also gives the game away in his language, such as how he describes the two sides of the “panels” that will debate, describing the science-defending side as “institutional orthodoxy” and the crank side as “independent dissent.” I saw right through that framing.

Kirsch also notes:

Importantly, every participant must disclose financial and institutional conflicts of interest — grants, patents, royalties, or advisory roles. Transparency about motive is a precondition for trust.

I’m game for this, but only if everyone on the antivax side also discloses how much they make selling supplements, publishing Substacks, doing social media (such as YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram), serving as expert witnesses, and the like.

But what about Kirsch’s evidence?

Now, let’s get to the evidence that Kirsch marshals to claim that refusing such debates is “unscientific”:

See:

Public debate is good for science which was an editorial in Science, of all places encouraging debate.Here is the actual science behind the recommendation to debate:

Effective strategies for rebutting science denialism in public discussions.That paper has been cited over 204 times in the scientific literature.

So science says you don’t run from debate challenges.

The first article was written by H. Holden Thorp, the editor of Science, in early 2021, just as mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines were starting to be distributed. It is an opinion piece. From my vantage point in 2021 after years of dealing with science deniers (and even more so since), Thorp is rather naive:

The days of going to a Gordon Conference or Asilomar and having a confidential debate about scientific issues are gone, and that’s for the best because those gatherings were not diverse enough and excluded a lot of important voices. These days, the public can access debates about science regardless of where they take place, so the medium isn’t so important anymore. What matters is getting to the right place in terms of the science—deciding what the question should be, the appropriate way of answering it, and the correct interpretation of the data. For many scientists, public debate is a new frontier and it may feel like the Wild West (it may well be). But rather than avoiding such conversations, let the debates be transparent and vigorous, wherever they are held. If we want the public to understand that science is an honorably self-correcting process, let’s do away once and for all with the idea that science is a fixed set of facts in a textbook. Instead, let everyone see the noisy, messy deliberations that advance science and lead to decisions that benefit us all.

I’m all for letting people see the messy deliberations that advance science, but, again, that’s not what antivaxxers like Kirsch are about. They’re about casting doubt on science that they don’t like, using whatever disinformation techniques they deem necessary, be it cherry picking studies, distorting data, producing bad science of their own, or attacking the scientists defending current scientific understandings. Thorp was correct that the “old days” were not diverse enough and could exclude important voices, but they had the advantage of forcing those with contrary positions to actually try to bring the data needed to cast doubt on existing science and support their positions. As we used to like to say (and I still like to say) scientific evidence talks, bullshit walks. That’s still true. It’s also important to remember that all science denial is arguably rooted in conspiracy theories, and data alone in debates of this type will not dispel conspiracy theories.

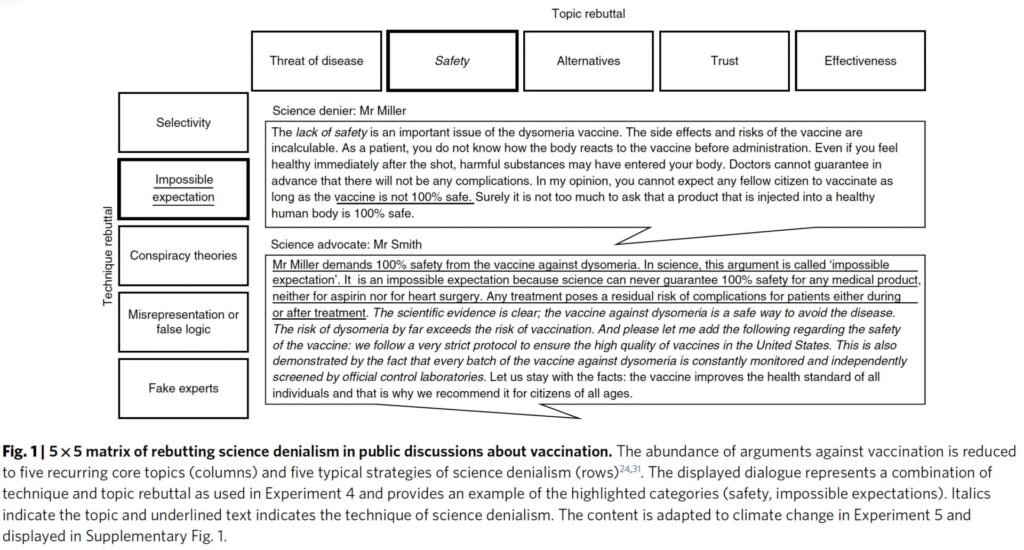

The second reference cited by Kirsch is a bit more interesting—and provocative. I can see why it appealed to him, as he is not the first antivaxxer whom I’ve seen citing this paper. In any event, it’s a 2019 paper in Nature Human Behavior by Philipp Schmid and Cornelia Betsch and, contrary to Kirsch’s characterization of it, it doesn’t quite declare that refusing debate challenges is unscientific. Rather, it’s a detailed discussion of how to effectively rebut claims of science denialists in public discussions, which include debates. As an aside, I can’t help but find it rather amusing how, by citing this paper, Kirsch seems to be implicitly admitting that he is on the side of science denial. That’s because this study is all about the effectiveness of two primary proposed techniques for refuting science denial in public discussions. Indeed, one chart is particularly useful. It’s a matrix of arguments against a hypothetical vaccine:

The five domains above, or techniques of denial, have become pretty well accepted in misinformation research, with the mnemonic FLICC (Fake experts, Logical fallacies, Impossible expectations, Cherry picking, and Conspiracy theories). Now here’s the thing. This study is not just about whether engaging in public debates with science deniers is effective; rather it’s about how to engage in public discussions, which include debates. Indeed, in the introduction, the authors explicitly state their purpose:

Beyond the question of whether to attend the discussion at all, advocates for science around the globe lack empirical advice on how to respond to a science denier in a public discussion.

Rather, the authors recognize the problems with scientists joining in such discussions and is meant to test various strategies for debunking misinformation as it happens. It’s more expansive in that it is not referring to staged debates, but to any public discussion in which a scientist is involved and encounters scientific misinformation. The authors are quite clear, noting that scientists have ignored the question of how to effectively counter the arguments for science denialism for too long and acknowledging a need for scientists to publicly debunk misinformation:

Researchers have now increased their efforts to focus on how advocates for science can inoculate individuals against misinformation before they encounter it20,21 and how misinformation can be corrected once individuals believe it22,23. A third option is to counter arguments of denial at the very moment that they reach an audience; that is, rebutting deniers in public discussions24. We will focus on this third option.

The authors also note the not inconsequential risks of this approach:

However, public discussions also entail risks for the discussants. Bad performance can, in the worst case, serve the opponent’s cause27. Moreover, backfire effects in attempts to debunk misconceptions23,28,29 lead us to question whether publicly rebutting misinformation is useful and successful. These backfire effects are most likely to be found among audiences whose prior beliefs or political ideologies are threatened by the advocate28,30. For example, attempts to correct misconceptions about vaccination in an audience with low confidence in the safety of vaccination28 can ironically reinforce the misconception. The same effect occurred among US conservatives (who strongly object to governmental regulation regarding climate change) when there were attempts to debunk misinformation about climate change30; that is, when they received information that eventually might lead to regulation. This fear of governmental regulation has also been discussed as a cause for US conservatives distrusting scientists on the topic of vaccination14. These risks make it difficult for science advocates to decide whether they should participate in a public discussion at all19, potentially leading to the absence of advocates for science from a discussion (henceforth referred to as ‘advocate absent’).

It turns out that a combination of techniques probably works better than a single technique. That being said, the purpose of this study was to test two techniques: Topic rebuttal or technique rebuttal. Topic rebuttal is a simple concept: Rebut the claims using knowledge of the topic, by overwhelming the denier with good scientific evidence (cite and explain well-designed and executed experiments and studies) and/or explaining why the claims and evidence presented fail as science (e.g., weaknesses in design, cherry picking of evidence, misrepresenting evidence). Technique rebuttal is one of my favorites: Namely expose the deceptive rhetorical techniques being used (e.g., point out how the denialist narrative is a conspiracy theory, how the denialist is using deceptive or emotional rhetoric, etc.). I tend to like technique rebuttal because I’ve become a fan of “prebunking”; i.e., inoculating audiences against denialist arguments by exposing them beforehand to knowledge about the techniques of denial involving rhetoric, distortion and cherry picking of evidence, conspiracy theories, as well as why specific commonly used denialist arguments are wrong.

The experiment was carried out by six online experiments involving exposure to denialist arguments ± subsequent exposure to technique or topic rebuttals. Most of the experiments involved vaccination, but one involved human-caused climate change. Primary outcomes included, among others, intent to perform a behavior recommended by science (e.g., to be vaccinated). In all the experiments:

In all the experiments, participants first received an interview with a science denier. Participants were then randomly assigned to the following design, determining the rebuttal condition: 2 (topic rebuttal versus no topic rebuttal; between subjects) × 2 (technique rebuttal versus no technique rebuttal; between subjects) × 2 (time of measurement: before versus after the debate; within subjects) mixed design. Depending on the condition, a science advocate: was absent from the debate; responded to the denier by using topic rebuttal or technique rebuttal; or responded with a combination of both strategies (Fig. 1 provides an example of the materials used in Experiments 1–4 and 6).

And:

First, we analysed whether the denier influences the audience’s attitude towards and intention to perform the respective behaviour. Second, we analysed whether technique or topic rebuttal are effective strategies for reducing the denier’s influence and whether the combined strategy is more effective than the single strategies. Finally, we explored whether the influence of denialism and the effectiveness of rebuttal strategies are functions of the audience’s prior beliefs or political ideologies.

Without going into the weeds of the details, the authors did this experiment using nearly 1,800 subjects and found:

An internal meta-analysis across all the experiments revealed that not responding to science deniers has a negative effect on attitudes towards behaviours favoured by science (for example, vaccination) and intentions to perform these behaviours. Providing the facts about the topic or uncovering the rhetorical techniques typical for denialism had positive effects. We found no evidence that complex combinations of topic and technique rebuttals are more effective than single strategies, nor that rebutting science denialism in public discussions backfires, not even in vulnerable groups (for example, US conservatives).

And:

As science deniers use the same rhetoric across domains, uncovering their rhetorical techniques is an effective and economic addition to the advocates’ toolbox.

OK, so the results of this study suggest that not responding to science denial leads to bad outcomes, with science denialist arguments casting doubt in the audience about science. It is one study, and Kirsch is using it the same way as another “COVID contrarian,” Byram Bridle, did in 2023, falsely characterizing Timothy Caulfield’s refusal to debate him as being “not following the science.” Also, amusingly, the authors of the study include one huge caveat:

We acknowledge that in some situations contextual factors may still force the advocate to avoid participation (for example, the format of the discussion is not serious or personal safety is at risk31). However, with regard to the effectiveness of messages in conventional contexts, not turning up at the discussion at all seems to result in the worst effect. There may be one exception to this: if the advocate’s refusal to take part in a debate about scientific facts leads to its cancellation, this outcome should be preferred21,51 so as to avoid a negative impact on the audience.

In other words, let the antivaxxers find another patsy if they can. More importantly, the authors note:

Also, as can be seen in five of the six experiments (Fig. 2), the debate usually had an overall negative impact on attitudes.

In other words, even if we science communicators show up to “debate,” the overall effect of denialist arguments on the audience will usually still be negative towards science. All we can do in such debates is to mitigate this negative effect. That’s why the wag in me would turn it around on Kirsch and say that this study could be used to support not agreeing to a debate like his, because (1) refusing might mean that the debate never takes place and (2) if the debate takes place the best that the science communicator could expect to accomplish would be mitigate the damage of denialist arguments. If you accept the results of this study, you have to accept that the end results of such debates will not be to increase support for vaccination in the audience!

Moreover, although I don’t have any objective data to support this conclusion, my personal experience suggests to me that, if there are no science communicators present to “debate,” such events held by science deniers tend to attract almost exclusively those already predisposed to the science denial being promoted; i.e., they become just another echo chamber. That is, of course, not good. Echo chambers can radicalize further. However, the event will be much less likely to win any “converts” to the science denial cause than a debate. (I’d love to see someone study this question with rigorous methods, but just thinking about how to do such a study gives me a headache.)

Thanks, Steve. I haven’t reviewed this study since 2023! Also, I still find it amusing how antivaxxers and science denialists cite this study obsessively when in fact, depending upon your interpretation and proclivities, the study can be used to justify debating science deniers like Kirsch or refusing to do so.

But what about Dr. Mike. Clearly, he chose to debate, and he chose to do so in a format designed to disadvantage the one who is “surrounded.”

Dr. Mike vs. 20 MAHA stans: Is it really about the science?

Before I start this part of the discussion, here again is the YouTube video of Dr. Mike’s debate with 20 MAHA supporters, for those of you who want to watch all nearly two hours of it. (Unfortunately, the video won’t let me embed it.) I also note that at the beginning of the video Dr. Mike notes that he’s surrounded by 15 RFK Jr. supporters. So much for 20, I guess. The exact number doesn’t matter that much, though.

My first observation was that Dr. Mike was quite effective at attacking specific points made by MAHA fans. Multipole examples stand out. For example, in an encounter with a woman who comes across as a typical “MAHA mom,” Dr. Mike pushes back against claims that doctors just want to keep their patients sick, so that they can make money. But first, he acknowledges her perception that doctors treat patients like “we’re kind of dumb” by conceding that this still can happen, before he pivots to asking the woman what she thinks of RFK Jr.’s longstanding (and not infrequent) claim that doctors are incentivized to keep their patients sick, asking, “Does that improve your relationship with your doctor or not?” The woman answers (at the 37:28 mark):

MAHA supporter: I would have to hear the context.

Dr. Mike: That’s the context.

MAHA supporter: Well, but I mean like the whole thing because one thing that I’ve experienced a lot with Bobby is that people get sound bites and they don’t hear the entire interview and the entire dialogue and then they peacemeal it and then they go that man.

Dr. Mike: Yeah, people people do do that with things, right? What’s a way that he could have been saying that in in a genuine way? Well, he in a genuine way.

MAHA supporter: Well, I think he was I I can’t speak for him. Sure. But my experience of Bobby is that he is a genuine, compassionate, kind, caring human and he takes his work very seriously and his commitment to ending chronic health disease and making sure children are healthy and adults are healthy is very very important to him. So, but if I heard that, I I probably would have been like, hm, I want to understand more about where he is coming from because it doesn’t line up for me that he would just generalize that all doctors are doing that. But in context, he might have been referring to something.

Dr. Mike: So, if one of the participants here that are surrounding us uh came up to me after the show and said that you’re a liar and everything you say is untrue, that perhaps could be said in a nice way?

MAHA supporter: Oh, well, I would probably think that maybe there’s something going on.

Dr. Mike (interrupting): Or called you a bad mother. Wouldn’t that hurt?

MAHA supporter: I’ve been a lot of things. It would make me think for a moment like, do you know me? Do you know what I do? Do you know how I am? Do you know my professionalism?

Dr. Mike: That’s how I feel as a doctor when Secretary Kennedy says that to me. He says we’re interested in people keeping people sick for profit. I don’t even take a salary to work as a doctor anymore. The YouTube stuff is so successful. I really am showing up for my patients pro bono because I want to help people. I’m here pro bono. I flew here myself for free because I want to give you the best information.”

One could look at this exchange as Dr. Mike skillfully using technique rebuttal, pointing out that RFK Jr. is positing, in essence, a conspiracy theory that doctors are in it to keep patients sick so that they make more money, although wisely he doesn’t use the term “conspiracy theory.” However, he goes beyond that to make an analogy to try to win the empathy of the MAHA mom by comparing RFK Jr.’s conspiratorial accusations about physicians to accusations that the woman is a bad mother, emphasizing that we physicians feel the same sort of emotional reaction as a woman accused of being a bad mother. After all, being a physician is central to our identities, just as being a mother is central to the identity of many women. Attacks on something that is central to our identity hurt, even more so when they’re not true. Then Dr. Mike skillfully lays the groundwork for what comes next:

Dr. Mike: And you said Secretary Kennedy is well researched.

MAHA supporter: Yes.

Dr. Mike: He goes on the podium and he says inaccuracies all the time. And look, everyone’s allowed to make mistakes. I’m not about gotchas. I’m not that guy. But when you say, back in the day, kids who had diabetes almost never existed and now one in three kids have diabetes, it’s a lie. One in 300 kids have diabetes. So like, how much do I as a YouTuber have to fact check Secretary Kennedy, the director of Health and Human Services, before he comes out and says, “I messed up. I need to tell you the truth, and I’m getting the numbers wrong so often.” When does that happen?

You and I know, of course, that the answer is: Never. RFK Jr. is an inveterate liar, and I am unaware of any instance when he’s admitted that a claim that he’s made, such as the one Dr. Mike discusses above, was in error. Of course, the question then becomes: Did Dr. Mike move the needle with this woman? The answer is, sadly, no. Instead of answering Dr. Mike’s question directly, she pivots to whataboutism and moves to COVID:

MAHA supporter: That’s a really good point. I don’t know. I guess we’d have to go back also to during COVID when they made these really outrageous statements that weren’t true. Either go back because because we there have been mistakes and…

Dr. Mike (interrupting): I have—I have multiple videos on my on my YouTube channel including podcasts where we talk about every mistake we made—I made—during the pandemic, because ultimately it’s about trying to figure out how to do better not to score political points.

And thus ended that exchange. To summarize, Dr. Mike employed empathy to try to get the woman to understand how doctors feel when RFK Jr. accuses them of all sorts of horrible things (like intentionally keeping patients ill so that they can profit and, although it wasn’t mentioned in the exchange above, intentionally making children autistic or even killing them with deadly vaccines, again for profit and ideology). Then he used his topic knowledge about diabetes to cast doubt on everything RFK Jr. says in a devastating fashion. It didn’t work to sway this woman, of course. A single exchange, not even one as effective as Dr. Mike’s, is likely to change the mind of a die-hard MAHA stan. At best, it might lead the MAHA stan to view Dr. Mike with less hostility. However, those watching who are not die-hard antivaxxers or MAHA stans could well be favorably influenced by Dr. Mike’s arguments, although the study cited by Kirsch could suggest that all Dr. Mike accomplished is to have decreased the negative effects on the acceptance of science-based medicine caused by watching 15 MAHA fans take turns going at Dr. Mike with science denying rhetoric.

There were a number of other instances where Dr. Mike, using a combination of topic rebuttals, technique rebuttals, and use of empathy to win over the audience, simply tore apart MAHA claims. In one instance, he explained why one of Dr. Peter Attia’s frequent claims is hugely overblown, which was particularly satisfying given that his opponent was acting as though he knew more than physicians. In another, when an opponent went on and on about doctors receiving pharma payments but couldn’t answer Dr. Mike’s questions about how we know how much money doctors receive from pharma. In response, Dr. Mike completely agrees with him that financial transparency is very important, after which he goes on to say, “Let me help you.” (I realize he was trying to be empathetic, but this was first class shade.) He then discussed the 2010 law called the Physicians’ Payments Sunshine Act, which requires disclosure of financial relationships between doctors and hospitals with pharmaceutical and device manufacturers. (BTW, if you look my name up, you’ll see that I receive no money from pharma. My name doesn’t even show up because, as the lookup site says, “Providers that have not received at least one payment in the past seven years will not appear in the search.”) He then reemphasizes that transparency is important and points out how there is no financial transparency in MAHA, as most MAHA influencers don’t have to report their financial relationships with, for instance, supplement companies or law firms suing for vaccine injury. A final example occurred when Dr. Mike agreed that opioid manufacturers got off far too lightly for having promoted opioid use and contributed to the opioid crisis.

You get the idea. A lot of what Dr. Mike did was not about the science. It was about values. It was about finding common ground in terms of values and then using that to point out where RFK Jr. is leading them astray. As you can see, though, it didn’t work with a hardcore “MAHA mom,” but it likely did at least make her less hostile to him, while making it more likely that observers might be swayed by Dr. Mike’s arguments.

Revisiting “debates” with science deniers

So what does this all mean? Am I a convert to the value of live public debates? Obviously, no. However, I am not as hostile to the idea as I used to be. Indeed, I think that Schmid and Betsch actually made a really good point near the end of their paper (you know, the one Kirsch cited so approvingly):

In relation to this, a third general take-home message is that advocates who take part in debates should not expect too much for their efforts. Therefore, facing deniers in public debates can be only one building block in the concerted effort to fight misinformation. Other recent approaches try to fight misinformation by pre-emptively providing laypeople with the ability to identify false information themselves20,21,52. For example, in a study conducted with Ugandan primary school children, researchers taught 10- to 12-yr-olds how to separate misconceptions about health treatments from facts52. Such educative approaches are in line with psychological research that attempts to inoculate individuals against misinformation20,21. The goal of inoculation is to make individuals aware of the arguments of denial before the actual information is obtained and to provide them with the ability to come up with counter arguments. An inoculated audience may be less susceptible to the arguments of deniers and the effects shown in the present experiments may be weaker in such an audience.

The way I look at it now is this way. Debating science deniers is a long run for a short slide that has a number of potentially devastating pitfalls. Because of that, it’s not for me, although I recognize that others might disagree. However, if you’re going to do it, you need to go in with your eyes open and train in a manner reminiscent of the pre-fight training montage from your favorite Rocky movie (metaphorically speaking, of course). Schmid and Betsch’s study appears to show that it makes little difference if you use one, the other, or both techniques; so it is best to go with your strengths, as they themselves state:

Still, being in a public debate with a science denier requires diligent preparation. It may seem like an endless universe of potential misinformation that is difficult to anticipate. However, analyses revealed that most topic arguments fall into five core categories and that deniers use the same five techniques to make those arguments appealing (Fig. 1; ref. 24). Hence, if they implement only one strategy (topic or technique rebuttal), advocates need to prepare only five key messages that address the core topics or techniques. It is important to note that we did not test all possible topics and techniques and that the effectiveness of the strategies may vary with specific topics and techniques. Nevertheless, training in technique rebuttal seems especially valuable as the techniques are the same across a broad range of scientific domains13,24, whereas the topics vary across domains (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, technique rebuttal is the more universal strategy in the fight against misinformation. Applying only one of the strategies may seem less complex; however, doing so successfully during an ongoing discussion will still require sufficient training.

I would tend to disagree with one thing though. This study aside, I would argue that, if you’re going to go into such a “debate,” you need to develop a high level of both topic and technique knowledge, even if you plan on primarily using technique rebuttal. Technique rebuttal can only take you so far in combatting a Gish gallop. You need to be able to point out at least one or two glaring errors in the Gish gallop in order to bolster your credibility when you go for the technique rebuttal pointing out that your opponent is doing a Gish gallop.

As we head into 2026, I think it’s important for those of us trying to counter the tsunami of misinformation that is now coming from “inside the house,” so to speak, given that the federal government is now controlled by antivaxxers and science deniers to play as much as possible to our strengths. It’s equally important to take heed to Harry Callahan’s advice in Magnum Force and know your limitations. In other words, I’m happy to let Dr. Mike do his thing on YouTube, for instance, and podcasters to do their thing to communicate science (I’m a pretty good podcast guest, but have no clue how to do my own podcast), while I do my thing here.

Finally, perusing the literature, the depressing realization that I come to is that we desperately need better data, experiments, and trials of techniques of countering misinformation and disinformation. I’ve long resented how little in the way of academic reward engaging in this work, either as a hobby (me) or as an academic pursuit yields. I’ve referred to how much of the scientific community looked down on Carl Sagan’s work last century, and that disdain, although it’s greatly abated since I started two decades ago, is still there. Unfortunately, with the cranks firmly in control of the federal government and, in particular, the NIH, funding for misinformation research, which was always inadequate, is now nearly nonexistent. Yet the need has never been more acute, leaving us in the meantime to do the best we can with what we have and to do what each of us does best.